- Home

- Rebecca F. John

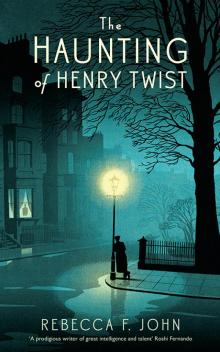

The Haunting of Henry Twist Page 12

The Haunting of Henry Twist Read online

Page 12

‘Shall I tell them, at work?’

‘Please,’ Henry said, and he wondered then if that was the last word he would say to all the people who used to fill his life: please. Please don’t tell anyone … Please don’t mention … Please don’t think … Please don’t assume … He stopped begging the last time his father hit his mother, and now, here it is again – a thing so ugly, and yet so often necessary. There is much, though, that Henry will endure for Jack, if tested. He knows this. And begging – for a man who, as a boy, watched his mother lie and cheat his father, then scream for pity as he beat his response into her – is not such a small sacrifice.

As he scrapes the last lick of shaving cream from under his jaw, he hears a scuffling at the back window which tells him that Jack is home. Every day now, Henry wakes to find him gone then waits through the dawn for him to return, dirtied and exhausted, having completed the first part of his working day before most of London blinks awake. They have settled into this routine easily, quietly, without once discussing what it means. Neither man has questioned that Jack must come and go via the kitchen window, clambering up and dropping out into the little yard in the early dark before checking in all directions for spectators of a crime not committed. The bicycle he uses to get to work they conceal behind the coalhouse and, sure he does not want to hear the answer, Henry has not queried the acquisition of it. He does sometimes suspect, though, that Jack cannot remember his previous work because he never had any. He is altogether too resourceful for a law-abiding man.

Henry would happily go on forever this way, knowing and not knowing, but he is aware that today Jack will want to discuss their situation: as he left this morning, he had whispered to Henry, ‘Later. It’s important.’

There is a thud as Jack drops onto the kitchen floor, and a breath afterwards he saunters into the hallway, a frozen lump of something meaty hung over his shoulder. With a flick of one arm, he throws it forward and catches it in both hands, presenting it to Henry with a wide smile. ‘Dinner,’ he says.

As Henry cleans his razor and carries the bowl back into the kitchen, Jack follows him, talking fast and loud, as he always does when he’s been at the docks. At first, Henry had thought this would disturb Libby, but it does not seem to break her sleep. Perhaps Jack’s voice slides into her dreams and keeps her safe from nightmares.

‘Do you know what I was thinking earlier? I was thinking I want to go to the cinema. I’ve never been, you know. At least, not that I remember. And there’s this film I’ve heard of, all about puppets, and –’ He sees the look on Henry’s face and stops. ‘Of course we can’t go together, but … I don’t know, we could each buy a ticket. Sit a couple of rows apart.’

‘It’s an idea,’ Henry answers.

‘But not possible.’

‘I don’t think so. Maybe if we go to one of those theatre shows, where the girls –’

‘Do you want to?’ Jack asks.

‘Not really.’

As Henry turns to lower the bowl into the sink, Jack loops his arms under Henry’s and presses his own palms to the other man’s chest. Henry inhales the salty smell of hard labour on skin before releasing that same long exhalation he makes whenever Jack touches him – part fear, part relief – and listens with closed eyes, frowning gently, as Jack speaks into his hair.

‘Last night,’ he says, slowly. ‘I dreamt about a woman.’ Henry waits. ‘A hell of a woman. And the house she lived in: the biggest, oldest house you could imagine, with a garden in the front and children playing there. Two boys. Two small boys. And she stood at the door watching them, this woman. And laughing.’ Henry feels Jack smiling. ‘And she was so happy just to watch those boys. So damn happy …’

‘What did she look like?’ Henry murmurs.

‘Kind,’ Jack answers. ‘The sort of woman who would make a good mother.’

‘What else? Describe her.’ Henry holds his breath, waiting for the details which will tell him whether the dream was Ruby’s – some hope she clung to as she died and passed on to Jack, translated into pictures – or whether the dream was just that, an ordinary dream, a messy collection of empty thoughts gathered up together into a story.

Jack rests his chin on Henry’s shoulder. ‘She was fair,’ he says. ‘Fair-haired, blue-eyed.’ And Henry deflates a little, relieved. He is not ready, yet, to admit his beliefs to Jack. Perhaps he never will be. Perhaps it is only he who ever need know.

‘Do you think she was real?’ Henry asks. ‘Someone you knew, before?’ He has not considered until now that there might be a wife, children, who wake up every day and plead for God to bring Jack Turner back to them. Jack, he guesses, is what? Twenty-seven? Twenty-eight? It is possible, likely even, that there is a fair-haired, blue-eyed Mrs Turner mourning her husband somewhere in London right now, and he sees her himself then, projected in miniature onto the window-pane before him, like a tiny film. He sees her standing on the door, watching her boys play, but she is not smiling: her face is undone by the endless crying, and there is a rip in her stockings she has not noticed, and she has curled one side of her hair and forgotten the other, and Henry knows what her grief is like. The idea turns him cold.

Feeling his shiver, Jack pulls him closer and kisses the newly smooth line of his jaw. Henry does not have the strength to tell him to stop. Or why he should stop. Initially, though, he does resist Jack’s touch: he always does. He stands taller, clenches his fists, readies himself for a fight. Then he softens as Jack’s hands move over him, as strong and weightless as wind off the surface of a cruel sea; as natural as that; as essential. He lets Jack draw him around, around, until they are standing face to face, and Jack catches Henry’s head in his hands. ‘No,’ he whispers. ‘She’s not anyone.’ His lips graze Henry’s. ‘Do you believe me?’ And Henry nods, he nods, because there is Jack’s mouth, on his, and all of Henry’s own words are suddenly contained within it. He has given them all over to this man, the man his wife chose, the body she fell into, the soul she replaced with her own, and Henry loves him, just as Ruby would expect him to. Just as hard and uncompromisingly and mercilessly as Ruby would expect him to.

He grabs Jack’s collar and forces him against the nearest wall. ‘I believe you,’ he says. And he kisses him again, his arms tight around Jack, his shirt pulling across his shoulders as he battles the urge to lash out, because this, with Jack, is an equal mix of need and honest, core-deep fright, and his body hasn’t learned yet how to reconcile the two.

‘Close your eyes,’ Henry orders. ‘You’ll spoil it otherwise.’

‘Spoil what?’

‘Wait and see.’

Henry sits at the head of the bed, propped up by the wall behind him. Between his legs, back to his chest, Jack is sprawled: a warm, casual weight, the sheets wrapped tight around the narrow angle of his hips. They have waited until dark for this, of course, but still Henry drew the curtains when midnight struck and they undressed, peeling off yesterday. To their right, the fire expires with a long chorus of snaps and fills the room with curls of dense, bitter-smelling smoke. Jack sniffs it in.

‘I like that,’ he says. ‘That’s a good, real scent.’

‘Aren’t all scents real?’ Henry replies.

‘I don’t think so. Not the ones you only remember.’

‘What about love you only remember?’

Jack thinks about this, and as he does Henry slides a hand tentatively towards his heart: he is cautious still about these simple intimacies. He counts the beats through the layers of muscle and tissue, skin and hair – steady.

‘I suppose love you remember is still love,’ Jack decides. ‘It might even be more real in retrospect; more felt.’

‘That’s a wise thing for a man with no memory to say.’

Jack tips back his head so he can look at Henry. ‘Perhaps,’ he says, smiling that wide smile, ‘I was a wise man. Perhaps I was a scholar. Can you imagine that? This handsome and clever. If I was rich too, I’m sure there are women in every corner of Engla

nd crying for me.’

Or men, Henry thinks. It is Jack, after all, who has taken the lead in this … Henry can’t bear to call it a love affair, even in the privacy of his own mind. Since that moment when he felt along Jack’s ribs for breaks, Henry has left it all to him: every choice; every chance. And it was Jack who first kissed him, not the reverse; Jack who first pulled him free of his clothes; Jack who got into his bed as though it were a normal thing.

‘Aren’t you afraid?’ Henry asks.

‘Afraid of you? There’s nothing to be afraid of in you. The only person you scare is yourself.’

‘How do you know that?’

Jack shrugs. ‘Call it intuition. Call it a gut feeling. Call it whatever the hell you like.’

‘And what about this?’

‘Call this whatever the hell you like. Naming it something isn’t going to change it.’

‘What if someone called you something else?’

‘Like what? A nancy? I couldn’t give a damn.’

Henry shakes his head. ‘I don’t believe you.’

‘I am that I am, Henry. I am that I am.’

‘Who was it that said that?’

Jack lifts Henry’s hand off his heart and kisses each knuckle. ‘I think it was God.’

Henry’s father had employed God in his every argument with his wife. If God had meant you to be a slut, why did he invent marriage? If God had wanted you to have more children, he’d have provided you with them. If God didn’t want me to teach you a lesson, why did he make me stronger than you? Henry tries to remember a time when he’d heard his father talk about men, men like them, but he can’t. Perhaps he could not speak of them. Perhaps the very thought made him physically sick. But then, they must have encountered at least one, on all their walks together through the city, Henry a small boy ducking from every innocent wave of his father’s hands. Henry steps his mind through his childhood, checking every corner, every shop, every green inch of parkland he can recall, but there is nothing. For a while, it seems his father never interacted with another man, let alone a nancy.

And then Henry half remembers an incident on the street below his bedroom window: he had watched with eyes wide, trying to breach the darkness, the soft knuckles of his right hand pressed to his teeth. He could smell the musk of the curtains and the cold off the glass, and he could hear, beyond the silence of an empty house, the gentle thud of repeated punches absorbed into a helpless body, and the wind.

It had been one of his mother’s men. One Henry’s father had discovered and dragged home to beat in front of his wife. Afterwards, he had been lifted off the pavement and carried slackly away, and Henry’s parents had clattered back inside, shouting and clawing.

‘I only do it to remind you.’

‘Of what?’

‘To want me.’

‘If God had wanted me to want you, he’d have made you more beautiful.’

Henry had not needed to hide halfway down the stairs to hear this exchange. It was shoved up at him through the floorboards. It echoed off the hard crack of a slap. It rained down on him like an assault of hailstones, and even then he did not understand it. He knew his mother was beautiful, on the outside at least.

Libby snuffles and Jack sits up to check on her. The tendons in his neck shift as he stretches to see over the cot’s bars, and Henry puts a hand to their movement before pulling Jack to his chest again.

‘She’s fine,’ he says. ‘Besides, you can’t just move about like that in the cinema. People will miss the film.’

Jack settles back and closes his eyes, understanding Henry’s intentions now. ‘So, now that we’re in our seats, old man …’

‘I’m going to let that one slide,’ Henry says.

‘Please do,’ Jack replies, flicking his eyes open momentarily to send Henry a wink before wriggling into a more comfortable position, the back of his head cradled by Henry’s sternum.

Henry clears his throat and begins. Already, he feels an idiot, but he knows that this is the sort of playfulness Ruby would have enjoyed, and he’s sure Jack will, too. ‘The seats are too small,’ he says, barely above a whisper. ‘Our knees are pushed up against the seats in front, and we’re trying not to move so that we don’t shake the row. At first there’ll be chattering. Then, the words ‘Pathéscope presents’ will come up, and as everyone quietens down, the hissing and crackling of the film will fly over our heads and hit the screen, and what was just a wedge of grey light will be the opening scene: people or a train or fields.’

‘Or puppets,’ Jack adds.

‘Or puppets,’ Henry agrees, but he does not like the idea. He sees himself and Jack, wooden-faced and hooked up to strings, blundering this way and that at the invisible direction of what they think to be instinct, because – they are controlled, really. They are moving at someone else’s bidding. It has not escaped Henry’s attention that, were they truly welcome amongst the Bright Young People, had they been born into such easy wealth, no one would question the relationship they seem to be building. He has heard about the nightclubs and the private ballrooms. But he has heard, too, of the arrests, and he knows the poor don’t come out unscathed.

He finds himself combing his fingers through the tighter curls just above Jack’s neck. ‘And –’ No, he won’t tell Jack anything of the possibilities out there for them. How can he, when he doesn’t believe they really exist?

‘Carry on,’ Jack prompts.

‘And as the film goes on,’ Henry continues, ‘you’ll find yourself starting to forget you’re even there. It’ll be like you’re standing inside it all, like you’re a completely different person, like you could be …’

His voice drops to almost nothing.

‘… anyone at all,’ he says. ‘Like you could be anyone at all.’

On the pavement outside Henry’s Bayswater Road flat, soaked through to her underthings by the small rain that has been falling all day, her hat drooping, her make-up running, her shoes being steadily ruined, Matilda Steck stands tall and rigid and sick. Her umbrella hangs loose in her right hand, the black canopy still extended but turned to the ground now, crumpled on one side and sheltering nothing and no one. She ought to be cold, but she does not huddle into her coat or rush for cover. She does not think. She is nothing presently but anger, which shakes her body like an approaching Tube train.

She had been coming to tell Henry about her plans; she had been coming to tempt him away from Ida before he fell into her trap; she had been coming to ask him, finally, if it was time for her to leave Grayson, whatever the consequences. As she skipped up the front steps to Henry’s door, her hopes were pinned to a proud man, a good man, an honest, respectable, untouchable man. Seconds later, she stumbled back down those same steps having glimpsed, through a gap in the curtains, a sight which collapsed her every hope.

There, lying ensconced in each other, were two bare-chested men. And there they remain. One fair, the other dark. One well-built, the other slighter. One wide awake and talking, the other drowsy and descending into sleep. Both an insult to God Himself. And one of them, at least, happy for the first time since that January morning when the world ripped his wife away from him.

CORRESPONDENCE

Pen gripped between stiff fingers, she bites words into the paper – long spikes and crude curves replacing her usually mellow hand. She stands hunched over the table, loath to pull out one of the four chairs and settle; loath, in fact, to do anything which might bring her comfort. She is ready to roll her anger out over days, weeks. In this moment, she is certain she will never know happiness again.

How could she? Despite her best efforts, the world has denied it her.

She scratches three short sentences through the paper and into her table top, scrawls her signature, and stuffs the letter into an envelope without rereading it. Sealing the envelope, she splits the skin of an index finger, but rather than sucking it dry, she drops the letter onto the table and squeezes more blood from the cut. She allows a red bead t

o fall and burst over the paper then, whilst it is still wet, she sweeps it quickly lengthways with a thumb – for the drama of it. She does not let her tears dilute the drying stroke.

Eventually, a boisterous sob escapes her, fracturing the silence and Matilda stops, breathless, and sinks to the floor, letting the noises come. Around her, the flat is in darkness. She did not stop to turn on a lamp. She ran all the way from Henry’s, ankles twisting, coat snagging. She watches the windows tremble with rain and waits for Grayson to come to her. And barely a breath passes before he is stumbling from their bedroom, eyes small, hair stabbing outwards, pyjama trousers twisted sideways around him so that he appears, as he steps towards his hysterical wife, to be a contorted doll, his body facing in one direction, his legs in another.

‘Gray,’ she manages to howl between sobs, the one syllable stretching ridiculously.

‘Yes. Yes,’ he says, ‘I’m here.’ And he crouches in front of her and holds her knees while she struggles to keep her chest from heaving like furiously pumped fireplace bellows. He holds her, though he knows where she must have been at one o’clock in the morning. And, when she is calm enough, Matilda presses her hands over her husband’s, because it is not only for Henry that she is crying. Not only for Henry. Grayson was two hours late home from work again this evening.

‘What is it, love?’ he whispers finally, once her tears are falling silently. The ‘love’ makes her stomach crunch in on itself like a balled fist.

‘Everything,’ she answers. ‘Everything, everything, everything.’ Grayson is afraid to question her beyond those ‘everythings’. Instead, he humours her. He coos and shushes and strokes. ‘That bad?’ he says. ‘Why don’t you get some sleep, then? It’ll all seem better in the morning.’

He lifts her and, wrapping his arms around her middle, steers her to bed. He does not disturb the bloodstained letter on the table. He does not see it. He is busy, unpeeling her sopping clothes, pulling her into her nightdress, kissing the parting of her perfectly straight, silver-toned hair. Even before the guilt of the last few weeks blanketed him, he had always admired the smooth silvery sheen of Matilda’s long, brown bob. It was – is – he thinks, the best parts of her shining through.

The Haunting of Henry Twist

The Haunting of Henry Twist