- Home

- Rebecca F. John

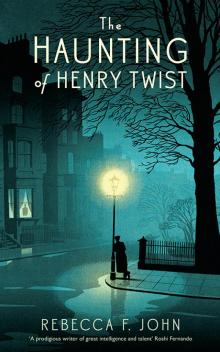

The Haunting of Henry Twist Page 15

The Haunting of Henry Twist Read online

Page 15

Henry had wished then that he’d had someone to fight for. He’d wished hard for that. And now he has Jack, right here with him, to fight for. But he doesn’t know how. He’s too angry. He’s too scared.

‘Can’t you see it?’ Matilda fumes. ‘Can’t any of you see it? You two especially –’ With a jabbing finger, she indicates Muriel and Lillian, who gape blankly back at her. ‘You’re embarrassing yourselves. Really, you are. Would you like me to explain why that is?’ She whirls around and points first at Jack then at Henry. She times her revelation perfectly. ‘He’s his man,’ she declares finally. ‘His man. Do I need to carry on? Do I? Do I? Do I?’

She repeats the challenge until somebody stops her.

‘You do not,’ Monty says quietly, his face stern. ‘You do not and you should not.’ Then he too stands and, placing a careful hand to her back, says, ‘You’ll regret this tomorrow, Tilda.’

In the few short moments that follow, Henry observes them from what feels like a great distance: Monty steering Matilda back to her chair and setting it right for her; Matilda lowering herself onto it mechanically, as though the part of her brain which moves her has ceased functioning; Grayson sneaking away to retrieve fresh drinks rather than admonishing or questioning Matilda. Henry imagines again that he is the man behind the projector at the cinema, and that the people before him are just tricks of light which he alone has the power to turn on or switch off. He brightens their colours in his mind, only to fade them to nothing. He tries to recollect every last detail he described to Jack – the first words on the screen, the crackling sound of the reel – so that he can replay them for himself, in slow methodical order, because it might be the only way to keep hold of his control.

Jack does not move. Henry does not move.

Henry wants to hurt Matilda.

One of the girls on the ground speaks: perhaps to ease her own discomfort, perhaps to ease everyone else’s. Either way, she chooses the right words. ‘My cousin Wally has a similar set-up himself. He keeps it quiet for the most part. His buddies have never seemed to mind, though, you know. You two shouldn’t be so coy.’

There is a wallop of silence before Monty starts to laugh.

‘But … It’s not true!’ Grayson says, handing out glasses and settling back into his chair.

Were he not rattled, though, he would offer the place to one of the ladies – Henry is positive of that much. Grayson is a gent. Henry peeks at Jack from under his hat brim. Jack shrugs in response, lips twitching into a flash-fast smile, there and gone again. Henry removes his hat, to give himself something to handle. Then, finally, he speaks.

‘Actually …’ he says.

And that’s all he needs to say. Matilda rolls her eyes and slumps backwards, vindicated but somehow all the more empty for it. Grayson opens his mouth and closes it, like a child blowing bubbles. Monty reaches out and clamps a hand around Jack’s knee – Jack being nearest to him – and as he does, the two queens excuse themselves and amble away in search of more suitable men.

‘Well, I can’t say I was expecting that,’ Monty says, the words coming slowly. ‘But, there we are. It would be a tiresome existence indeed if we were all of us predictable.’

‘Is that all you’re going to say?’ Matilda asks, her voice like flint. She does not turn to Monty for his answer.

‘Perhaps,’ he suggests, ‘you should head home, Tilda. Why not come back in the morning? I’ll be here, supervising the clean-up after this mob. I could do with your help.’ He speaks as though to a child, all the while eyeing Gray, who eventually takes the hint and hooks his arm under Matilda’s to persuade her up.

And, much to Henry’s surprise, she leaves without uttering another sound.

Henry, Jack, and Monty sit in silence then, gazing after the Stecks as they meander away through the constellations of crownless monarchs who lie about the garden, wide skirts and velvet cloaks spread over the grass, legs flung out, cigars and cigarettes releasing matching smoky wisps into the sky as they curl, the Bright Young People the newspapers so passionately love and so readily hate, body into body. Their wedding vows are forgotten. Their homes and their children and their everydays are a far-off joke. They are shaping a ruleless reality, but Henry knows that he and Jack do not belong within it.

This is it for them. Tonight must be freedom enough.

He glances in Matilda and Gray’s direction only twice, to make sure they really are leaving. Before they have even crossed the garden, Henry notices, Gray releases his wife’s arm. By the time they reach the gate, they are walking two or three feet apart, and when they step through it onto the pavement beyond, they move like two strangers, happening into each other’s lives for only the briefest of moments.

And that, Henry thinks, is sad. That, regardless of the situation, is very sad indeed.

Later, someone tires of the lethargy which has pervaded the party and drops the gramophone needle to restart the music. As couples redistribute themselves around the garden – dancing more desperately now, less discreetly – Monty takes Henry aside and sits him in a quiet corner. Backside to the earth, Henry pushes his shoulders hard against the uneven stone-work: hard enough to leave little dents in his flesh.

‘Have you thought about this, properly?’ Monty asks.

‘I’ve done enough thinking, Monty.’

‘And you’re sure?’

‘Yes.’

‘Then why is it,’ Monty probes, ‘that you’re facing away from me?’

Henry turns to Monty, to tell him that he is not ashamed; that he had not been avoiding Monty’s regard; that he had been watching Jack, who, visible transiently through the shifting gaps between revolving couples, is trying presently to balance three champagne flutes on his fingertips. But he stops himself. Monty has caught him unawares: the man has never looked so old. Henry studies the patches of discolouration which map the whites of his eyes, the pleats of skin folding down over his lashes. He wonders if he, too, has aged tonight.

‘Will he make you happy?’

‘Why do you care about us so much?’ Henry returns. ‘We’re selfish, every last one of us. Selfish and callous. And we don’t do a thing for you. Not a single damn thing –’

‘Yes, you do. You …’ Henry hears the wobble in Monty’s voice and locks eyes with him, challenging him for once to speak the truth. He can’t tolerate another secret. ‘You make enough noise to drown out the fear.’

‘Of what?’

‘The end, of course,’ Monty answers. ‘What else?’

Henry stops. He can’t respond to that. Not when he has ventured so close to the end himself. He understands Monty’s fear, he does, but …

‘Now tell me if he’ll make you happy. Henry.’

And Henry is about to say ‘yes, yes, yes’, but before he can utter a sound, a shriek goes up. Short but penetrative, its echo seems to knit itself into the air, where it lingers, another high-ceilinged tent, as panic begins below. One of the fairy lamps, knocked by an enthusiastic dancer, has swung too close to the greenery and as flames begin to spread, and women scatter away gripping their skirts, and men dash forward to make half-hearted attempts at dousing the growing fire, so Monty – young again – leaps up and lopes away across the garden.

Yes – that is the answer Henry had wanted to give. Yes. And for a moment, it had felt definite. As Monty rushes away, though, Henry loses his grasp on the word and, when Jack finally returns to his side, smiling, champagne flutes now artfully arranged in his slim hands, Henry’s bravery seeps away too. There will be no celebration for them. How can there be?

He jumps up. He tries, and fails, to speak. And then all at once he is running. Hat tumbling to the ground, tie flapping over his shoulder, he attempts to escape the party – the whole evening, in fact – at a sudden, unstoppable sprint.

Shoved aside, Jack lets the glasses smash to the ground. Then, retrieving Henry’s hat, he takes one long deep breath and sets off after him.

DOUBT

He

stops running only when he feels his lungs might burst. And even then, he does not stop walking. He strides on towards home, his head pounding, his breath heaving, his arms swinging as an imaginary soldier’s might. Henry knows that real soldiers do not move this way. In Belgium, those who still had arms to swing had long lost the drive to force them through such a pointless arc.

Behind him, Jack – the fitter of the two men now, though it might have been different once – matches his footsteps.

‘Nobody was angry,’ Jack says. ‘Come on, Henry. Did you think it could go any better than that, after what Matilda did?’

‘No.’

‘Then did Monty say something?’

‘No.’

‘Will you slow down? Christ, Henry!’

Henry stops and spins around. The two men almost collide. ‘Christ, Jack,’ he spits.

‘Christ, Jack? What do you mean ‘Christ, Jack’?’

Henry scrubs at his face with both hands, trying to ignore the reek of stale alcohol which fumes off them. He paces back and forth across the pavement, shaping more of a circle really in the narrow space. They are on Bayswater Road now, just a little way from the flat. A line of oak trees leads the way home, their branches tangled in their neighbours’ and casting a web of shadows onto the street below. Henry grips the black spears of the park railings in tight fists and, like a man imprisoned, rattles them until they make a deep, hollow-sounding twang. Then, unsatisfied, he turns and kicks at the nearest lamppost. There is a clang of shoe on metal and the light sways above them, but neither Henry nor Jack looks up at it. They’ve made eye contact now, and they cannot break it.

‘We shouldn’t have gone,’ Henry says, quieter this time.

‘I know.’

‘We can’t do it again.’

‘We don’t have to.’

‘But there are things, other things, like … work, and … I have to move out of the flat, and … Libby will have to go to school, you know? Libby will have to …’

‘Grow up.’

‘Yes. Grow up. And how can she do that, with –’ Henry stops and flicks his hand between himself and Jack: it trembles like an indecisive weather vane.

‘Two men,’ Jack whispers.

‘Two fathers,’ Henry whispers back. ‘And, what should we do, Jack … Jack. You’re not even sure that’s your name!’ He attempts a laugh, but it withers. ‘What should we do?’

He hasn’t the strength to stop the tears coming. He’s had too much to drink, and too little sleep, and he’s been collecting them for too long a time. They gather and fall. Jack shifts forward, slides a hand around Henry’s back, and pulls them together chest to chest.

‘Don’t,’ Henry says.

‘There’s no one around,’ Jack murmurs.

‘Someone might pass.’

‘No one will pass.’

Jack wraps both arms around Henry and clings to him as he sinks to the ground. On the pavement, he speaks over Henry’s shoulder, not caring if the world hears his words.

‘We’ll work it all out,’ he says. ‘I know what you think. I do know, Henry. I don’t know if you’re right, I don’t even know if I believe it’s possible, but I do know what you think, all right? All right?’

Henry does not answer immediately. He attempts instead to think his way back to last year, when Ruby was here and Libby was not and he recognised the shape of his life; when it was travelling in the direction he had pointed it in. Already, the reality of that past is being distilled. Each day or week or month he spent with Ruby is being condensed into a singular picture or sentence.

‘How?’ he asks eventually.

‘Because I know you,’ Jack says. ‘I know what’s inside you, all right, right down to your bones.’

And though this is the very first thing Henry wants to hear, it is perhaps the very last thing Jack should have said, because, sitting on the steps outside the flat, hatted and coated, a small brown leather suitcase at her feet and an angry woman’s letter folded into her pocket, is Ida Fairclough.

Morning has not yet begun to open up the darkness and, in the near-black canopy of shade the building creates, she is invisible. In the cavernous quiet of half past four, though, she can hear almost every word Henry and Jack speak to each other as their sentiments echo along the street. She can hear, too, that Henry is crying. She cries with him, silently, hunched around Matilda’s letter, because she understands its jumbled message about deviants and perversions now, and because she understands that, wherever he is seeking his comfort, this man, this proud man, is crumpled on the cold ground aching for her sister. Hurting for her. He is made weak by his need for Ruby. Whatever the circumstances, Ida wishes someone would ache for her that way.

She peeps over the wall. Henry and Jack are still huddled into each other on the pavement. She lifts her suitcase and tiptoes down the steps, considering slipping away and returning another time – she is sure Daisy would put her up for a night or two – but just as she turns in the opposite direction, she is spotted by the man she knows only as Jack.

‘Hello?’ he calls, rising.

What choice does she have then but to turn back and walk towards these two so rudely discovered lovers?

‘Henry,’ she says when she reaches them. ‘I am sorry to sneak up on you in the middle of the night. It’s just that, I received a rather dramatic letter … But first, how are you?’ She passes her suitcase into her left hand and offers him her right.

‘Ida,’ he responds dumbly. They stand, Henry and Jack, side by side, shuffling from foot to foot like bashful children. And though Ida feels she has caught them in the midst of a naughty scheme, she is determined not to show it. She is too proud to allow any sort of hysterics in the street.

‘Shall we?’ she says, indicating the way but arranging her hand awkwardly, as though she is a shop girl demonstrating the quality of some item of clothing.

And: ‘Yes,’ Jack answers when Henry does not. ‘Yes, we should.’

In the front room, Ida stands in the curve of the window whilst Jack builds a fire. Henry, balanced on the edge of Ruby’s shaky dressing-table chair, thinks that it is not cold enough for a fire. He understands, though, that Jack needs a task to occupy himself with. They are uncomfortable, all three of them. Their words, when found and blurted into the silence, are tinny and disconnected – as though they are arriving along a telephone wire.

‘It was Matilda, wasn’t it?’

‘Do you need to ask?’ Ida says, allowing herself a tiny smile. ‘She obviously fell for that look of yours.’

‘I don’t think it’s about –’

‘Of course it is,’ Jack puts in. ‘It’s about you.’ The flames are catching now, jumping towards and away from each other, towards and away. He stands, stretches, and settles on the settee, positioned between Henry and Ida. He is ready to play referee.

‘I’ll have to beg your forgiveness for a second time,’ Henry says, his voice low but his head high. ‘And in as many meetings.’

Ida lowers herself onto the windowsill and removes her gloves, then lays them out flat beside her, smoothing the creases away. She crosses her legs. ‘Perhaps,’ she says, ‘an explanation, rather than an appeal.’

‘You’re not furious?’

‘I might be. I don’t think I should decide before I’m made aware of the details, though, do you?’

Henry hides his face in his hands, trapping the sigh he releases. ‘How did you get to be so reasonable, Ida?’

‘Why shouldn’t I be?’

‘Your sister wasn’t.’

Ida smiles. ‘No,’ she says. ‘She wasn’t, was she? I loved that. Not that I ever would have admitted it … Anyway. I’m ready. I’m listening. Begin at the beginning.’

The two men share a glance and, feeling the privacy of it, Ida makes a show of peering around the room. There is still so much of Ruby here: the photographs on the mantel; a pair of black shoes placed next to the wardrobe; the bits and pieces scattered over the dressing tab

le; a diamanté and white-feathered headband hanging from the mirror there. Amongst these items Ida feels – at the back of her neck and through the hairs on her arms – a certain presence which, she imagines, many people would mistake for a ghost. She knows though that it is not Ruby who haunts her, but her own guilt. Ida Fair-clough begrudged her sister the life she chose. She was envious. And her envy made her stay away from the woman she so longs to reach now: a woman who is forever unreachable.

‘It was the day of the funeral …’

Ida takes a deep breath and straightens up. Then turns to Jack and nods. ‘Please,’ she says. ‘Carry on.’

And so he does. He guides her, move by careful move, from that night in January when he walked whistling away from Henry for the first time, through his every important recollection – their meeting at the costermonger’s cart, his muddled memories of what happened at the Prince of Wales, the lies he told to acquire work at the docks – right up to the moment when he and Henry decided to venture out to a party together. Some of it Henry has not heard before, and he sits, chin resting on the pillar of his forearm, and takes it all in.

Naïvely, perhaps, he trusts Jack to offer Ida only the appropriate details. It is clear that Jack wants to unburden him of telling the story, and Henry is grateful. He hasn’t the stomach for it. Not so soon after Matilda’s antics. Besides, he does not possess enough words to tell Ida all he wants and needs to tell her. He doubts there are enough words.

The Haunting of Henry Twist

The Haunting of Henry Twist